By Jonathan Wojcik

ENTRY 07: THE EMPTY MAN

By the next day, the group has experienced some ambiguously paranormal activity, pursued by a frightening presence the audience has not seen, and taken refuge in a cabin. Paul has continued to act strangely, and after whispering something unknown into Ruthie's ear, he vanishes into the blizzard outside.

So ends a fully 20 minute prologue before the film's current events; a move that a lot of reviews harp on, but I thought was interesting enough. Kind of like getting a whole bonus "prequel episode."

One day Nora's daughter Amanda (Sasha Frolova) disappears, and she leaves a bloody message written on a bathroom mirror: "the empty man made me do it." Naturally, James investigates with the skills he acquired over years of detective work. He finds a strange flier for something called the "Pontifex Institute" in Amanda's room, retraces her steps and eventually questions one of her close friends, Davara (Samantha Logan). He learns of the urban legend of the Empty Man, a being that can be summoned only if you find an empty bottle near a bridge and blow into it while you focus on his name. Empty beer bottles are in no short supply near remote bridges of course, and the whole friend group dared each other to take turns one night in the tradition of such ghosts and demons as Bloody Mary or Japan's Toilet Hanako.

The last time Amanda was seen after that night, she was whispering something to their friend Brandon.

With no other leads to follow, James tracks down the Pontifex Institute, where his investigation takes a turn for the much more bizarre.

Arthur happily expounds upon some fascinatingly strange theories on the nature of mind and matter; that thoughts and concepts are one with physical forces, that all things are connected by the mnemosphere, or "the sum of all conscious thought," and that "virus-like vectors" can facilitate transmission between the thoughts of individuals or even break the boundaries between what is imagined and what is reality. According to him, the Empty Man isn't a literal entity, but a "focal point for mental energies," a symbol they use to personify their principles.

A thoroughly unsettled James continues his hunt for Amanda from there, but someone appears to keep breaking into his home and he finds himself plagued by vague nightmares of pursuit by some unseen, monstrous force in flooded, decrepit maintenance tunnels. Believing the cult to be stalking him, he puts Nora up at a hotel room until further notice, and we happen to learn that the two were having an affair even before his family died.

This is where things go completely off the rails for James, when Amanda tells him that his entire life is a lie. She informs him that he's nothing but a psychic construct, like a tulpa, just a few days old and implanted with false memories. He naturally thinks she's speaking gibberish, but when he tries to contact Nora, he finds that she doesn't recognize his voice, his name or anything about him. Being forced in this manner to question his own reality is all the institute and the Empty Man need to overtake his mind, and he suddenly perceives himself in the sewer-like tunnels from his nightmares.

But does it work? When last we see James, he walks out of the Hospital room to find the Pontifex members bowing before him, and the movie ends.

MONSTER ANALYSIS: THE EMPTY MAN

"Cults" and "lovecraftian" entities feel fairly overplayed to me these days, but I still find a bit of intrigue in this kind of pseudoscientific "psychic energy" angle, the idea that there's somehow some deeply hidden faculties of the human brain that can interact with the universe in ways we cannot understand. It doesn't have any conceivably basis in reality, of course; I'm sorry to say that your brain is truly "just" trillions of cells chit-chatting with one another in the confines of your skull, and their "only" interaction with the world outside your body is through your external sensory systems, though that should be more then amazing enough, shouldn't it? Must we be so greedy as to demand even more? A human being is the sum of countless chemical process that underwent so much struggle, so much adaptation to a universe packed full of impending death and destruction that its advanced computational systems now know what I mean when I string these little symbols together into this sentence. I can type "banana" right here and the amoebas in your skeleton's attic will load up whatever data you need to remember what a banana is. That is MAGICAL. Why does anyone need psychic stuff?!

Still, it makes for a pretty fun story when we imagine the amoebas know more than we know that they know. That they can do way more than make you remember that I didn't type "pineapple," that's a different thing I just forced them to force you to think about. See? I'm practically a god already, and so are you! I guess that's precisely why it's scary to imagine unfathomably greater collections of organic data, capable of bridging gaps in reality we couldn't even imagine were ever there.

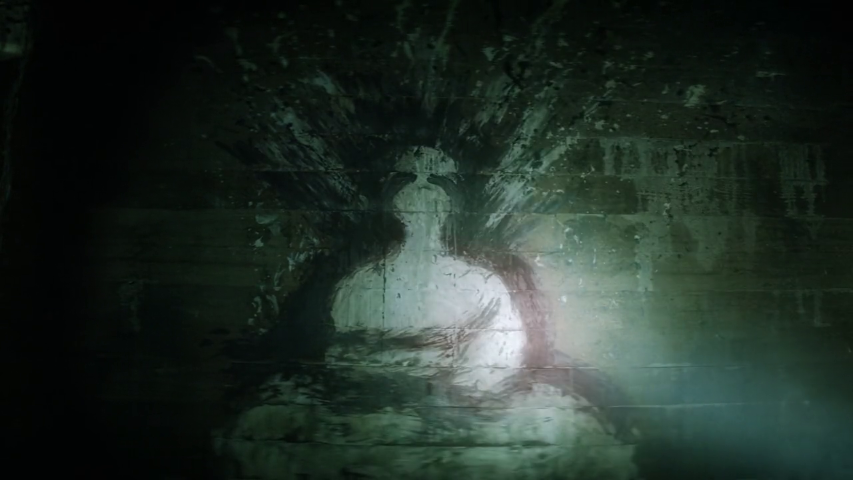

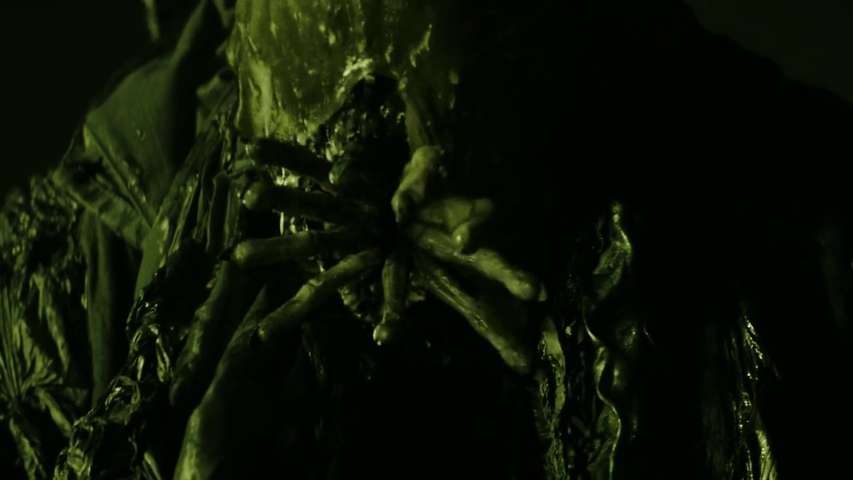

As far as these unfathomable psychic forces go, The Empty Man is a pretty cool one. I like that, at least within the movie there's no determining whether the being is part of the collective product of the mnemosphere or vice-versa, and the identity of that inhuman mummy is especially tantalizing. Was that in fact what became of an ancient human vessel? Is that the sort of evolution James may one day undergo?! It's a beautiful design, too, confirmed to have been based on the aesthetic style of one of my favorite painters, which I'll get to in a moment.

In directing the prequel film, David Prior clearly sought to tell his own original story and say something distinct from the books, but what that is, we don't really know. I've now seen review articles and internet comments interpreting The Pontifex Institute as a parallel to either new-age liberal progressivism or traditionalist, conservative conformity run amok, to fascism or socialism, to religion, the internet, pseudoscience, whatever the hell "wokism" means to some guy on twitter, and anything else the viewer fears about modern society. You're basically free to slap any label you want on these antagonists and make your own New Yorker cartoon of the whole thing.

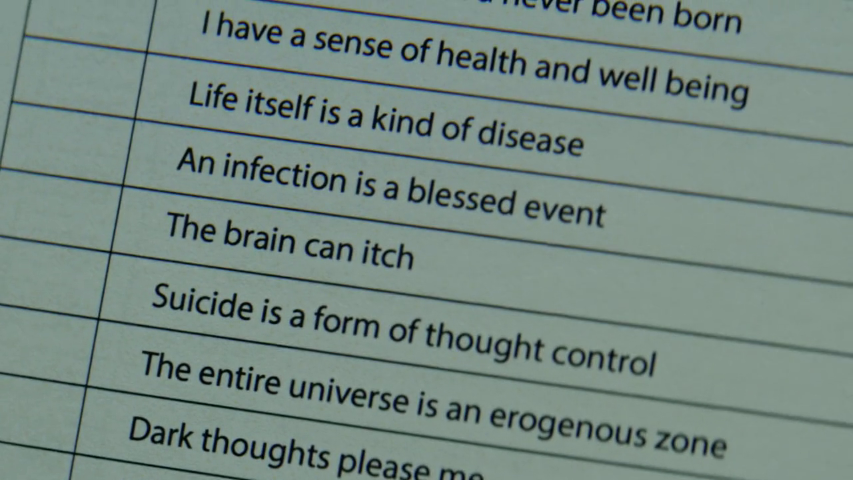

There's even a small following of LGBT reviewers who see something similar to Tetsuo at work; that the plight of James strongly resembles the pain and confusion of never feeling "right" about who you are or where you fit in, and that the Pontifex Institute can therefore be taken to represent either submission to conformity (returning to the closet) or the frightening first steps to re-examining your personal identity. On the other hand, there are also those who feel that the LGBT community are among the targets of this movie's social criticism - especially given that some of the Pontifex Institute's "application questions" are about gender - and I can't really argue with that, though it's difficult to argue with any given reading. Across multiple interviews, Prior has essentially said that nobody (at least as of one 2020 interview) has quite hit on his own thought processes, but that it doesn't mean anyone else is incorrect, either. It's a movie confirmed to have a deeper meaning, then, but not necessarily one that comes built-in. Like abstract art, it might be an intentional blank slate, deliberately inviting the viewer to construct whatever meaning resonates with them. Most positive reviewers admit to projecting their own feelings into this blank slate, and that's exactly what they've been enjoying about it; a refreshing break from the usual pre-packaged social commentary of so much other media.

NAVIGATION:

WAYS YOU CAN SUPPORT THIS SITE!

HOME