Intermission: Phage Facts

Bacteriophages are a vast and varied group of viruses which arose early in Earth's history to parasitize bacteria.

Bacteriophages are a vast and varied group of viruses which arose early in Earth's history to parasitize bacteria. As a virus, the bacteriophage consists of DNA within a complex protein capsule. This capsule drifts passively until it comes into contact with a viable host bacteria, injects its DNA into the bacterial cell, and replicates itself with host resources.

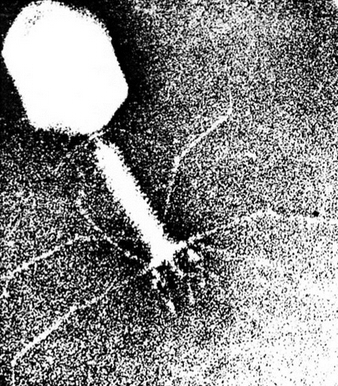

As a virus, the bacteriophage consists of DNA within a complex protein capsule. This capsule drifts passively until it comes into contact with a viable host bacteria, injects its DNA into the bacterial cell, and replicates itself with host resources. The most famous bacteriophages, characterized by both their "neck" and "legs" (tail fibers) are known as myoviruses. The podoviruses possess the "legs" but almost no "neck," while the siphoviruses possess an extremely long neck with stubby or absent fibers. Other bacteriophage groups may resemble ordinary, nearly spherical viruses, rods, ropelike strands, or in the case of the plasmaviruses, a form surrounded by a loose, bloblike "bag."

The most famous bacteriophages, characterized by both their "neck" and "legs" (tail fibers) are known as myoviruses. The podoviruses possess the "legs" but almost no "neck," while the siphoviruses possess an extremely long neck with stubby or absent fibers. Other bacteriophage groups may resemble ordinary, nearly spherical viruses, rods, ropelike strands, or in the case of the plasmaviruses, a form surrounded by a loose, bloblike "bag." Viruses are now known to have evolved from single-celled organisms and can properly be considered a form of life. As such, bacteriophages are known to be the most abundant form of life on our planet, even outnumbering their own bacterium hosts.

Viruses are now known to have evolved from single-celled organisms and can properly be considered a form of life. As such, bacteriophages are known to be the most abundant form of life on our planet, even outnumbering their own bacterium hosts. Bacteria ultimately determine life and death for the entire global ecosystem, but it is primarily phages which regulate bacterial populations in nature. Every single day, up to half of the bacteria in the world's seas are killed by phages, only to replicate themselves again by the next.

Bacteria ultimately determine life and death for the entire global ecosystem, but it is primarily phages which regulate bacterial populations in nature. Every single day, up to half of the bacteria in the world's seas are killed by phages, only to replicate themselves again by the next. Bacteria and bacteriophages are engaged in a constant, complex arms race, rapidly evolving weaponry against one another. Bacteria may even develop false, dummy DNA strands to fool phages and hide special proteins that chop apart phage DNA.

Bacteria and bacteriophages are engaged in a constant, complex arms race, rapidly evolving weaponry against one another. Bacteria may even develop false, dummy DNA strands to fool phages and hide special proteins that chop apart phage DNA. Before multicellular organisms evolved more complex immune systems of their own, they would have relied entirely on phages to protect them from infection.

Before multicellular organisms evolved more complex immune systems of their own, they would have relied entirely on phages to protect them from infection. The mucus membranes of animals are an exceptionally effective medium for phages to survive in. "Snot" is in fact so dense with phages that this is almost certainly one of its primary functions in our body's defense.

The mucus membranes of animals are an exceptionally effective medium for phages to survive in. "Snot" is in fact so dense with phages that this is almost certainly one of its primary functions in our body's defense. Research into medical use of phages faded upon the development of modern antibiotics. As antibiotics have proven to breed more resilient strains of bacteria, the concept of "phage therapy" has seen renewed interest in the medical community.

Research into medical use of phages faded upon the development of modern antibiotics. As antibiotics have proven to breed more resilient strains of bacteria, the concept of "phage therapy" has seen renewed interest in the medical community. Not all phages immediately replicate themselves and destroy their bacterial host. "Temperate" phages more often undergo a "lysogenic" reproductive phase, meaning that they harmlessly encode themselves in the bacterium's DNA and lie dormant there, replicating along with the bacteria for many generations. Should these bacteria begin to die off or sustain damage, the dormant phage gene or "prophage" will revert to its viruent form, constructing complete phages and bursting from the sick or injured bacterial cell.

Not all phages immediately replicate themselves and destroy their bacterial host. "Temperate" phages more often undergo a "lysogenic" reproductive phase, meaning that they harmlessly encode themselves in the bacterium's DNA and lie dormant there, replicating along with the bacteria for many generations. Should these bacteria begin to die off or sustain damage, the dormant phage gene or "prophage" will revert to its viruent form, constructing complete phages and bursting from the sick or injured bacterial cell. Most phages are temperate in our own body, hibernating in our normal, beneficial bacterial populations until the stress of a more hostile invader triggers their viral mode, or in other words, as our "good bacteria" die off, they unleash phages from their own DNA to battle "bad bacteria."

Most phages are temperate in our own body, hibernating in our normal, beneficial bacterial populations until the stress of a more hostile invader triggers their viral mode, or in other words, as our "good bacteria" die off, they unleash phages from their own DNA to battle "bad bacteria." During embryonic development, your immune system was bolstered by phages travelling from your parent's body to your own through the umbilical cord.

During embryonic development, your immune system was bolstered by phages travelling from your parent's body to your own through the umbilical cord.Further Reading:

Communication Among Phages, Bacteria, and Soil (PDF)

Communication Between Viruses Guides Lysogeny Decisions

Bacteriophages Encode Factors Required for Protection in a Symbiotic Mutualism

Bacteriophage Adhering to Mucus Provide a Non-Host-Derived Immunity