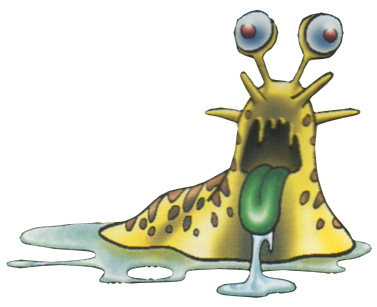

A PERSPECTIVE ON SLUGS.

Source

Slugs are great! Sure, the hypnotically swirled shell of a snail has an almost unreal whimsy to it, but that seems to be precisely why they enjoy such widespread acceptance in our popular culture. Once the very same animal is homeless and naked, it becomes much more divisive, much "grosser" and "creepier" in the eyes of far more people, with slugs seldom gracing anywhere near as many cartoons, fantasy paintings, lawn ornaments or "cuteness overload" blogs.

Perhaps it's for this reason that I was always drawn to slugs so much more than their shelled counterparts, or perhaps it's just that simple blobbiness that I find just a little more charming all on its own.

Source

It should go without saying, of course, that I'm not including nudibranchs or any of the marine slugs in this "gross underdog" equation, and they're a subject best suited to their own, distinct article anyway. Today we're just going to be talking terrestrial slugs, and in particular, my personal experiences with the terrestrial slugs of the United States, one of our few remaining conversation topics still untainted by despair and horror.

And before we begin...

What IS a Slug?

Source

Imagine keeping your most vital organs in a big, bulletproof backpack, and you'll have a handle on the life of a shelled Gastropod, or what we call a "snail." You can even pull the rest of yourself up into that backpack when you need to hide from predators, sleep through the hot day or just wait out a dry spell.

Unfortunately, that convenience comes with a cost. Your big, heavy backpack slows you down, limits where your body can fit, gives some predators something easier to grab onto, and you even have to keep building and mending the thing. A snail needs to intake a significant amount of calcium to keep that shell growing.

A slug, on the other hand, trades the advantages of the shell for pure freedom. It may be more delicate and more vulnerable to dehydration, but it can also go wherever it pleases, hiding itself in deep cracks or crevices to escape the sun. For the slug, the whole world is its shell, so long as it can haul itself back to its preferred hiding place before it gets baked by the sun every day.

Source

Taxonomically, the definition of "slug" becomes a little more nebulous. Some groups of Gastropoda contain both shelled and un-shelled members, while others consist of entirely one or the other, and there even exists a full spectrum in between, from snails with internal or partially internal shells to near-slugs with a mere flake of shell hanging off their rumps. Variable degrees of nudity have basically arisen all throughout the snails, and many languages never even bothered giving "snails" and "slugs" two different names at all.

Many slugs you may be familiar with, however, do fall under one major group, the genus Limax, which finally brings us to...

SLUGS I HAVE KNOWN PERSONALLY:

LIMAX MAXIMUS: The Leopard Slug

(Source)I grew up in Bel Air, Maryland, crammed up in the Northeastern sinuses of our continent, surrounded by fairly lush but fairly polluted forests, creeks and meadows. A debilitating fear, almost semi-reasonable in a lyme disease hot-spot, often kept me from exploring the wild as much as I might have really liked, but one of our most interesting animals frequently crawled right up to our front door.

Limax maximus literally means "biggest slug," and these handsomely patterned mollusks are among the three or four largest land slugs in the world. They were actually common enough that I took them completely for granted, assuming without a second thought that most of the world had slugs almost as long as a dollar bill. In truth, maximus is a foreign, invasive species generally found only along the damper, cooler coasts of the U.S, and it wasn't until I was trapped in Florida that I came to appreciate these nasty aliens.

Source

What makes the leopard slug interesting is the fact that, true to its spots, it's actually a fairly ravenous hunter. It will chew up vegetation of every sort, certainly, but it loves almost nothing more than the opportunity to slurp up an earthworm or a fellow slug; including its own kind. I actually learned the hard way - and have heard from others - that a leopard slug in captivity will choose to eat another leopard slug before virtually anything else, however lavish the feast and comfortable the habitat you may provide it.

...But for all that slow-motion savagery, Limax maximus exhibits by far one of the most beautiful reproductive rituals of any Gastropoda, a phenomenon I've unfortunately never been lucky enough to witness, but may still have a chance, since the species is as common here in the Pacific Northwest - the opposite side of the country - as it was around my childhood home, but more on that later.

PHILOMYCUS CAROLINIANUS: The Carolina Mantleslug

(Source)From a distance, the Carolina Mantleslug can almost be mistaken for a morph of the Leopard slug, and somehow, I'd never even notice them in my hometown until I revisited it with my wife, finding scores of them clustered around rotten logs and tree roots in Bel Air.

Little is written of Carolinianus's habits, but I know from experience that they aren't nearly so hungry for flesh as L. maximus, though they do grow almost as impressive in length and tend to be quite thick. The "mantleslug" moniker refers to the fact that in these slugs, the mantle extends to cover the entire length of the animal, giving them a smoother, "unbroken" appearance compared to many other slugs.

Though lacking the incredible mating dance of the leopards, mantleslugs possess the same "love darts" common to some snails; a chitinous needle injected by one slug into the flesh of a potential partner to deliver something similar to reproductive hormones. The full functions aren't really well understood.

VERONICELLIDAE: The Leatherleaf Slugs

I talk about these slugs a bit in my Florida article, but to recap, Florida was a pretty miserable environment outside a few interesting local species, and these became my favorite. I'd already lived there for nearly a year before I stepped outside one morning to find a half dozen of them scattered around the porch, and was downright ecstatic to see something I truly never knew existed.

These are another slug completely covered by their mantle, but while the mantle of Carolinianus is a thin, slimy membrane, the mantle of the "leatherleaf" is a thick, tough and rubbery shell that overlaps the actual "body" of the slug by quite a bit, as we see here. While the surface of the "foot" forms the entire underside of most slugs, the foot is little more than a "tread" down the middle of these mollusks.

Why this adaptation? Able to flatten out and cling hard against flat surfaces, this smooth, tough dome obviously offers a lot of protection against predators such as frogs, lizards and stinging insects as well as pretty decent camouflage. I became an expert in spotting these slugs from afar, but to most living things, they're all but invisible against a backdrop of leaf litter or tree bark. Defense, however, seems to be only the half of it.

Most of the large slugs I'm familiar with are more active the darker, wetter and cooler their surroundings. Peak summer heat can melt a Leopard slug like ice cream, and direct sunlight can mummify it in just minutes. Leatherleafs, on the other hand, seemed to thrive in hot, steamy Florida, and I could sometimes even find them slinking about hot pavement up to an hour or two after sunrise.

The secret to all this would seem to be in moisture retention. Whereas other slugs will smear your fingers with a thick layer of mucus, a leatherleaf feels only slightly damp and sticky, like a cat's tongue. This conservation of body fluid likely makes it much easier for these slugs to survive under conditions that would rapidly dehydrate other gastropods, trading the defensive qualities of a mucus coat for more physical durability to both predators and climate.

ARIOLIMAX COLUMBIANUS: The Pacific Banana Slug

SourceSo, after eight ghastly years in Florida and a slightly less ghastly year in the midwest, my wife and I finally found where we truly belong, and while we had a long list of reasons to seek out the cool, damp, cloudy, rainy climate of the Pacific Northwest, I should have always known I'd be happiest under the same conditions as Ariolimax, the holy grail of North American gastropoda.

Between the funny name and the striking color scheme, the banana slugs have long been a go-to limacid in popular culture. All my life, I'd spy them in cartoons, in comic books, in toys, in video games, even that lovely Harry Potter scene where Ron can't stop throwing them up and the unappreciative nerd didn't keep ANY of them.

I'd finally have my first encounter with these legendary beasts on a visit to Seattle, Washington in mid-2016, and seeing these fanciful, polka-dotted slimes in the wild for the first time felt like an encounter with a unicorn.

It was bittersweet, of course, because I'd have to learn the hard way that, despite my best possible efforts, these mountain-dwelling giants simply cannot handle a journey back to the hotter, drier wastelands constituting most of the rest of America.

Thankfully for my relationship with fruit-shaped mollusks, we would find ourselves living in Portland, Oregon by the end of that same year, and not only can I now visit them almost any time I want, but they don't vaporize when I bring them home.

That's not to say they're ubiquitous, of course. Though we live just twenty minutes from a sizable population of these slugs, their sensitivity to elevation is such that none can be found any closer to our own apartment, where temperatures reach just slightly higher and the humidity just slightly lower.

Source

There are actually three species of "banana slug" out here on the West coast, and together with some variation from one individual slug to the next, they run the full range of "banana colors" from a uniform bright yellow - most common in the California banana slug - to that gorgeous green-brown and black-blotched appearance of our local Columbianus. All three are important recyclers of forest litter, chewing their way through millions of tons of rotten vegetable matter per year, and are beloved enough by Northwesterners to have their own merchandise and sports mascot.

ARION ATER: The Black Slug

My first encounter with real, wild bananas in their natural habitat remains my most exciting slugsperience, but it was on that very same hiking trip that I encountered these similarly impressive oozers, actually littering the first stretch of the trail. Ranging from a beautiful red-orange to pitch black and with a fantastic gold "rim," A. ater actually has a lot in common with the leopard slug; it originally hails from another continent, it's made a bit of a pest of itself, and it's a semi-ferocious omnivore - even, so I'm told, eating banana slugs when the opportunity presents itself. Whether they're nearly as cannibalistic as L. maximus, I haven't yet seen...but the two I collected did mysteriously vanish on me, and it's entirely likely that they wounded one another in a gripping battle to the death somewhere deep within the dark underbrush of a twenty gallon terrarium.

LIMAX FLAVUS: The Cellar Slug

As exciting as Oregon's biggest and most infamous slugs have been, I'd discover a brand new personal favorite within our first few days in the state - and unlike Ariolimax or Arion, these "cellar slugs" turn up in our very own driveway.

Webbed in beautifully subdued shades of green with uniquely blue-tinged eye stalks, these ghostly slugs produce a distinctly yellow-green mucus from their backs - perfect "cartoon" slime - and even hatch from their eggs as green as grass clippings, fading into dim splotches as they grow. The common name, "cellar slug," comes from their close association with man-made architecture, thriving particularly well in sewage tunnels, basements and even moist enough bathrooms or kitchens. You may recognize that these are symptoms of an animal particularly suited to caves, much like house spiders, silverfish, cockroaches and countless other "urban" invertebrates. In Germany, changes to modern architecture and new sanitary practices have even left these poor, harmless goo-balls critically endangered, where once they commonly spread throughout old-fashioned breweries and earned the name bierschnecke - literally "beer slug."

I've heard from other Northwesterners that these are pretty much just the common "garden slug" around here, and I've certainly begun to find dozens, if not hundreds of them on the right nights...but they still feel like something special to me.

...And since they like houses so much, I got them one. I can confirm that they use it, too, though some of them also like to burrow beneath it, or even hang out just under its eaves.

TESTACELLA HALIOTIDEA: The Shelled Slug

SourceNamed for the tiny, nail-like shell on its rump, haliotidea boasts a magnificent resemblance to the moldy, severed finger of a corpse, and appropriately enough spends almost all of its existence buried deep in the soil, seldom seen by humans. Completely predatory, it feeds exclusively on live earthworms, and

...And then, not even one week after I originally posted this article in early March, I took a short walk just outside our Portland apartment one rainy, lukewarm night and spied none other than a suspiciously long, pallid slug on the sidewalk...then another, then another, and ultimately five of them in the same night.

This was an animal I'd always heard was "barely ever" spied above ground, something I could potentially go my entire life without encountering...and here were about half a dozen right outside our front door, bigger and weirder and spookier than I'd ever even imagined. If my first encounter with a banana slug felt like I'd just met a unicorn, this was like meeting a unicorn riding a dinosaur...though I get the distinct feeling that they're not so much rarely seen as rarely noticed. Not that many people are stopping to investigate the different kinds of slug they come across on the sidewalk - let alone in both the dark and the rain, which seems to be the only conditions that will drive them to surface.

So of course I kept them all, and my zombie fingers even happily gorged themselves on earthworms their first night in captivity. Actually something of a bloodbath, leaving some poor worms in gruesome bits and pieces I now know I've seen scattered on these same streets before. According to what little literature I've read, the slugs use a specially barbed, eversible radula to pull worms down their throats, and even "bite" through them as they pinch the end of the radula shut. Imagine a sock puppet completely covered in teeth, and you'll have a good idea of what's inside a shelled slug's mouth.

I can actually find zero mention, anywhere in all the vastness of the internet, of anybody ever keeping these killers as pets, so my attempts are going to be pure trial and error. As natural burrowers, I haven't seen too much of them since bringing them indoors, but I know they're there, often leaving fresh tunnels in and out of the moist soil of their enclosure.

...And speaking of tunnels now, you may have noticed that the bodies of these slugs taper towards the front, unlike the more bulbous anteriors of other slugs, and something that immediately struck me was how hard their bodies were. Though they can stretch themselves as thin as any other slug, they feel almost as dense and tough to the touch as a scrap of tire rubber, or maybe a damp strip of beef jerky.

These characteristics likely aid the Testacella in their fossorial existence; having nothing to actually "dig" with, they simply push their way through the depths of the earth, tapering out and repeatedly wedging those tough, rubbery bodies through the soil.

SLUGS I'D LIKE TO MEET:

SELENOCHLAMYS YSBRYDA: The Ghost Slug

By Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum WalesAnother soil-dwelling worm-eater, this slug spends so much of its time underground that it has entirely lost all pigmentation and any trace of eyes, much like the troglobytic fauna found in caves. It wasn't formally described until 2008, and was named "ysbryda" or "ghost" in Welsh.

HEMPHILIA: The Jumping Slugs

I've heard for years about Canada's "Dromedary jumping slug," which sounds exactly like some sort of animal a summer camp would make up to tease gullible children with, but it really is a slug with a camel-like hump - where it's partial shell is located - and an ability to "jump," or at least "violently squirm," which is almost like jumping by a slug's standards.This "jumping" is performed when the slug detects a predator, such as a slug-eating snail or a snail-eating beetle, and breaks up the slime trail these predators may follow.

My odds of ever seeing a jumping slug are now surprisingly high, as a single species can be found in Mount Hood, Oregon, just an hour from our current home...but the species is just rare enough to be under legal protection, and can't always be easy to find in Hood's enormous forests.

ATHORACOPHORIDAE: The Leaf Veined Slugs

SourceAn amazing variety of gorgeous, flat-bodied land slugs can be found primarily in New Zealand, and if I weren't so sure I'd wither up and die without Halloween, I'd consider becoming a kiwi almost entirely for these slugs and all those giant crickets. A quick google for this group will show you an amazing variety of shapes, textures and colors, but by far my favorite of all is this one:

Source

Have you ever seen a slug with SPIKES??? The adorable name of this adorable species is Putoko ropiropi and I want them more than I have ever wanted possibly any other living thing.

TRIBONIOPHORUS GRAEFFEI: The Pink Triangle Slug

SourceAnother, less "leafy" but nonetheless amazing member of the Athoracophoridae is quite common in New Zealand's senselessly large and less interesting neighbor, Australia, marked by a strangely three-pointed red mark, sometimes only a red "outline," surrounding the breathing spiracle on the animal's back. These slugs mostly graze on algae and lichen, and are known for leaving scribbly "graffiti lines" overnight on walls and fenceposts.

The Australian Pink Slug

More amazing is this enormous pink slug, growing up to eight inches in length and so closely related to the red triangle slug that it still hasn't earned its own separate latin name. These slugs are found exclusively atop Eastern Australia's Mounta Kaputar, a "sky island" supporting an ancient oasis of cool, moist forest surrounded on all sides by hot, dry plains.

The coloraton of these slugs has been described as "almost fluorescent" and "as bright pink as you can imagine." Pinker than any computer monitor can actually display. The slugs emerge "by the thousands" during the night to graze, and can still be seen creeping their way back down tree trunks into the early, misty morning. If I die before I ever see this, and I probably will, you'll know what my ghost is coming back for.