A Fly Every Friday, Duh!

FRIDAY THE 29th, JUNE 2018:

An Introduction to the Diptera

Tired of having written so little about biology over the past couple of years, I've decided to get back into the habit with a weekly series on my absolute favorite order of animal life, the Diptera, or flies. Can you believe a meager two-page countdown list on the subject was what I once considered one of my "biggest" site features? That barely qualifies for a hefty tumblr post these days! Since the smashing success of my pokemon reviews, my policy now is that if I can make a series out of something, there's never any reason not to.

Gladson Machado

So...flies. We don't know exactly which order of insects are truly the largest - it was long thought to be the Coleoptera (beetles) and may very well be the Hymenoptera (ants and wasps) - but the flies are quite likely in the upper two or three, having conquered the globe with over 120,000 described species and an estimated potential of over a million species. Obviously, the diversity of such a massive group can get downright mind-boggling, but today, for our first entry, we're just going to talk about the kind of fly most people recognize, like this housefly, Musca domestica!

Isn't it funny that, of all the winged things on Earth, these are the ones we just call "flies?" Other insects have to be dragonflies or dobsonflies or mayflies, and even birds don't get to be called "flies," despite being the first animals most humans tend to associate with flight.

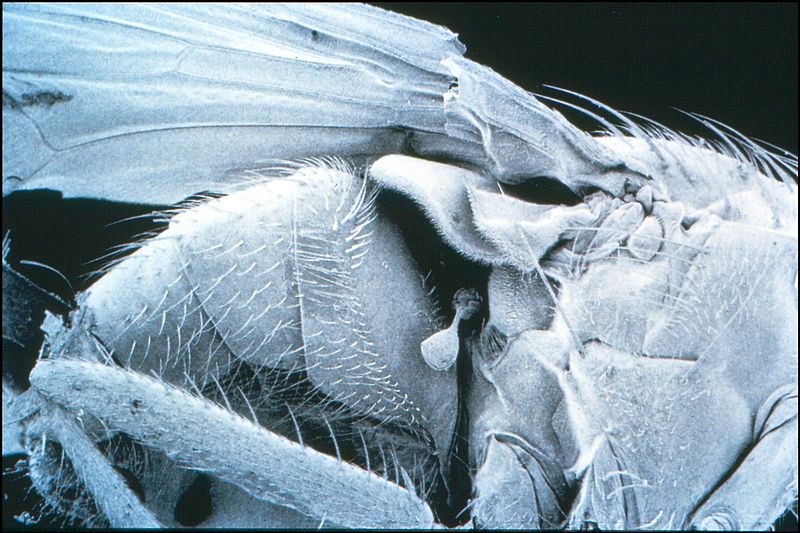

CSIRO

This is even odder considering that flies have fewer wings than the typical insect. Most groups, including moths, bees and the aforementioned dragonflies, possess two pairs of fully functioning, flight-capable wings, while beetles have modified their front wings into a cool set of pop-up shields and just a few insect groups have lost their wings entirely or never even evolved them.

Flies, and almost flies alone, have functional front wings and greatly reduced hind wings, hence the name Diptera or "two winged," but those hind wings are far from mere vestiges. Technically known as halteres, these tiny knobs buzz in tandem with the forewings and were once thought to provide only a sort of "counterweight" in flight, but we now know that's putting things far too simplistically.

The deeper reality is that the halteres are part of a sophisticated positioning system that allows the tiny insect to pull off aerial maneuvers more advanced than virtually any other flying organism. These dense knobs on their delicate stems are finely tuned to feel the force of the Coriolis effect as the fly turns or rotates its body on any axis, sending a constant feed of information to the animal's brain. Thanks to the halteres, a fly has a feel for its relative position, speed, weight distribution and surrounding wind resistance we humans can barely achieve with our most advanced navigational computers.

Only a single other insect group, the amazingly weird Strepsiptera, has ever evolved halteres of its own, modifying them from their front wings with no evolutionary link to the true flies.

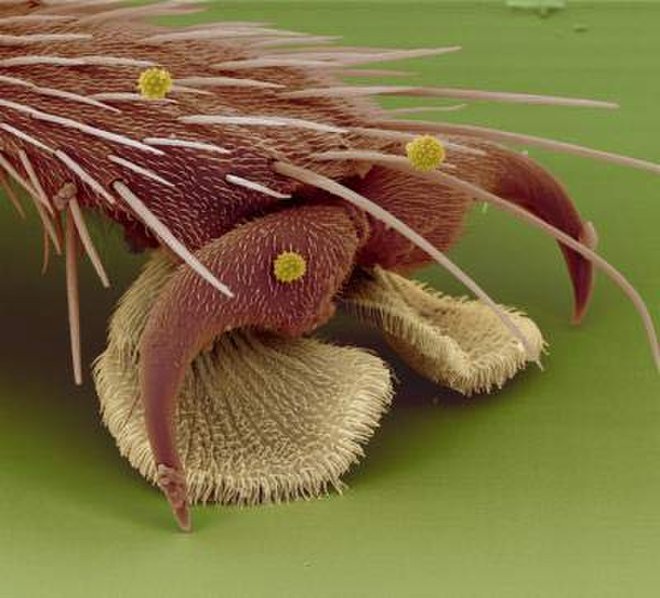

Stanislav Gorb

Those aerial acrobatics are important to an animal that may spend so much of its life upside-down, courtesy its incredibly sticky little feet. This is something many insects are capable of, but flies have once again pushed to an extreme. Each foot is equipped with two soft pads, the pulvilli, covered densely in fine, rubbery "hairs" with spoon-shaped ends. These setae secrete an adhesive manufactured by the fly from a mixture of oil and sugar.

Individually, this bond is fairly light; too light for the bristle or even the "glue" to become permanently stuck or left behind. It's the gentle stickiness of thousands upon thousands of setae per foot, and at least four feet always anchored at a time, that results in a collective grip strong enough that to take a single step, the fly must push against its tarsal claws to peel the foot back off your ceiling.

Brian V.

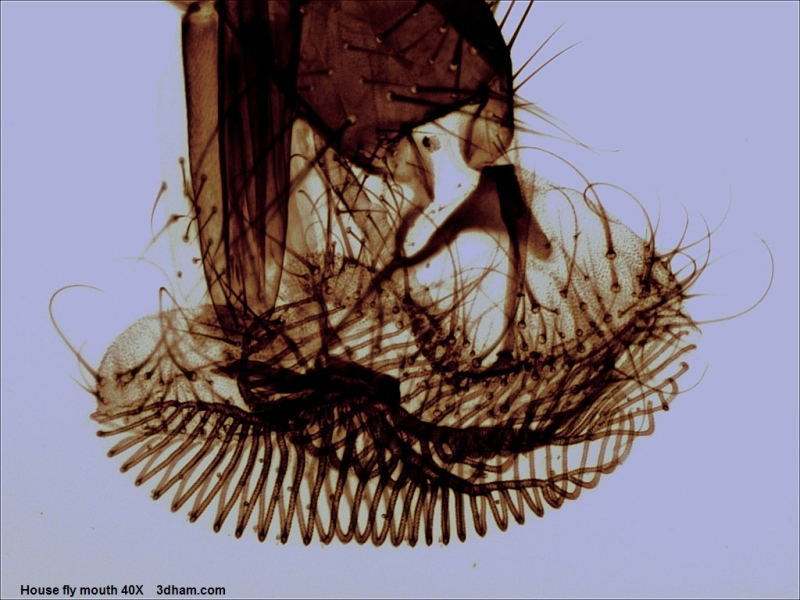

Halteres arent the only modification so unique to these insects, either. All flies are liquivores, incapable of biting or chewing their food, and those that aren't either carnivorous or sanguivorous possess an amazing "sponging" mouth system. What we're technically seeing here are the mandibles and the labella or "lips" of a typical insect fused completely into one tubular, retractable proboscis, easily my favorite feature, the end of which has evolved into an unusual "sponging pad."

John Alan Elson

This "sponge" is in two lobes, opening up like the covers of a book, with the esophagus between them and a set of hollow tubes called "pseudotrachea." Each tube follows along the inner edge of its lobe with 27-30 or more branches running to the outer edges of the pad, surrounding the actual mouth opening with dozens of ancillary openings. As it feeds, it also drools, its salivary secretions breaking down organic matter into a thick "soup" it can soak through these myriad channels.

You really can use any ordinary sponge to see how this system works. Place the sponge in a large puddle of liquid, press down on it, and watch it draw the liquid inside as it regains its shape. If you were to stick a straw into the back of the sponge, and continuously suck liquid out of it as you repeatedly sop up the puddle, then you would have perfectly recreated the mechanics of the proboscis. Please do not actually do this.

JJ Harrison

When not in use, the sponge is folded shut and most of the proboscis is drawn up into a gaping, hollow socket on the insect's head, and thank you, JJ, for capturing the clearest photograph I have ever seen of that. You can even see the seam where it folded! I have literally never known what that looked like until now!

This awesome shot also lets us move on to the fly's antennae. Common flies have what are known as aristate antennae. One segment, or flagellomere, is enlarged into a relatively massive paddle-like appendage, covered in fine bristles and pits, with a finer feathery feeler or arista branching off near the flagellomere's base. As with many other insects, these function mostly for smelling, but can also detect vibrations in the air - much like every bristle on the creature's body - and even serve as "ears." Personally, I just adore that big, triangular pit they can fold into, like an exaggerated skeleton nose!

Of course, the most famous facial feature of a fly are those enormous compound eyes, occupying much more of its head than in most other insects, or just about anything else alive on our planet. The typical fly has just enough eye surface, covering just enough of its head, that it can see clearly in almost every direction at once, and while not a survival feature per se, it also makes them look endearingly sympathetic to me. Downright sorrowful!

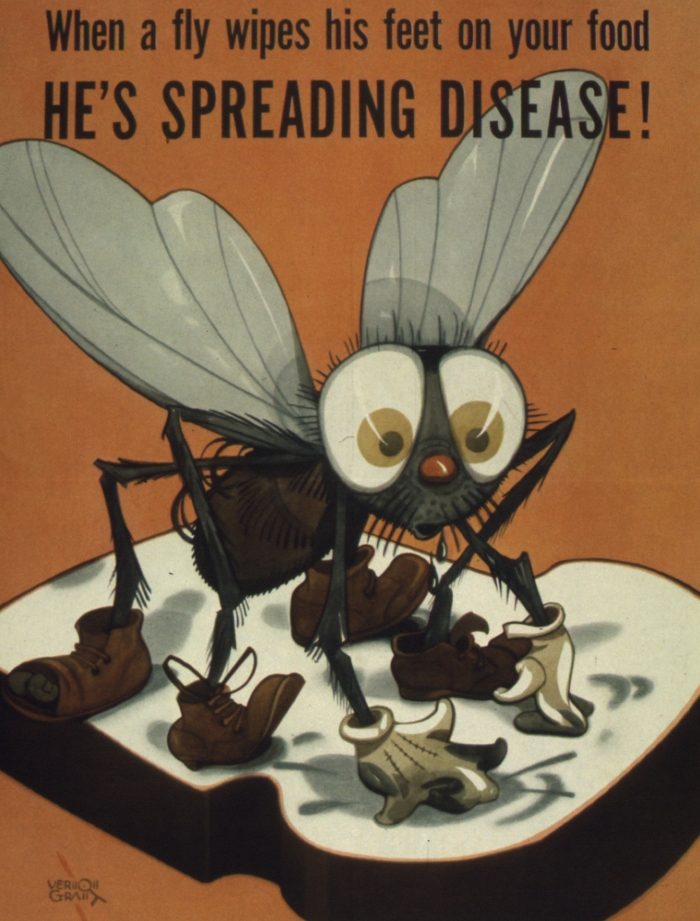

Unfortunately, flies are not sympathetic in the eyes of most humans. In fact, their "disgusting" image may rival only cockroaches, and unlike the Blattodea, your typical household fly really does swim with disease...though it's not without good reason.

Laszlo Ilyes

There may be just as many herbivorous, carnivorous and parasitic flies out in the world, but the family is known best of all for its scavengers, and no other land creature is so proficient in the consumption of decomposing waste. It isn't even a contest. Flies have monopolized the art of carrion eating to such a degree that their activity defines what we know as the "active decay" stage in the decomposition of a corpse. If something dies and flies can get to it, only an apocalyptic level of radiation or pesticide can prevent them from doing so.

There are even flies tiny enough to wiggle their way between grains of soil and into the most carefully buried casket. There are flies that specialize in nearly frozen environments and even flies that specialize in bone...but we all know it's not the adults, with their tiny little sponges, who are doing all that clean-up.

EYE OF SCIENCE / SPL / BARCROFT MEDIA

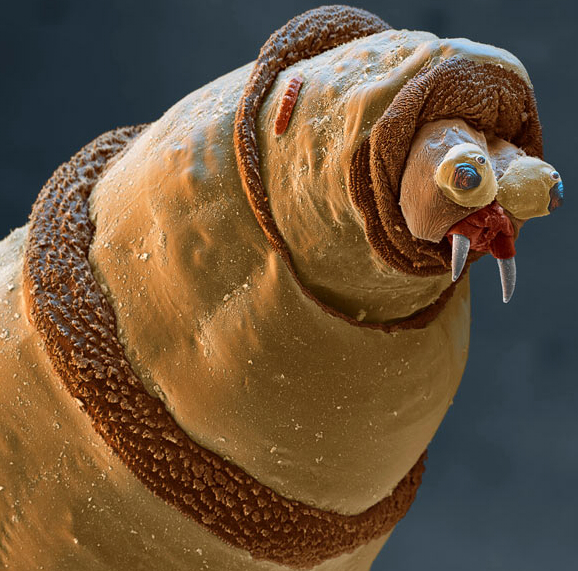

By now, I hope most of you have seen this world famous photo of what a maggot, a larval fly, actually looks like in closeup; like someone tried to make a hand puppet of a walrus out of parka that was already made from the flesh of a real walrus. It's bizarre and hilarious, but it's also elegantly efficient.

n

What's also interesting about a maggot is that it's technically adapted to an "aquatic" lifestyle. It does, after all, spend most of its time buried in wet, juicy meat, so in order to breathe, its respiratory pores are situated on its rear, a pair of dark spots you might mistake for eyes staring out at you from the surrounding rot. The "living drill" spends its existence face-first in food, snorkeling through its butt. Again, hilarious, but also terribly, terribly important.

A single female fly can lay around 200 eggs at a time, and may mate ten or more times in her brief life to produce a couple thousands when all is said and done. Each egg hatches within 24 hours, and larvae blast through their entire childhood in only about five days of constant meat-sucking and butt-snorkeling before they crawl away to pupate, emerge as adult flies, and may already find their first mate within a few minutes. Over the course of a few weeks, hundreds of staggered generations can reduce even the largest cadaver to little more than skin and skeleton, tens of thousands, sometimes even millions of microscopic mouths scrubbing every last cell of soft tissue from the porous surface of every last bone.

Something, I'm sure you've realized, has to do this. Neither vultures nor coyotes nor rats or slugs or worms or mildew can clean up a body so swiftly and thoroughly. The diseases potentially carried by flies are nothing compared to the outbreaks of contagion and wafting stench that we might suffer if these super-decomposers were removed from the equation, and neither could they perform this job so effectively if anything were different about their anatomy.

A long, long time ago, someone in a chatroom told me that they wouldn't mind the existence of maggots if they were simply "nice looking" - if they were some combination of more colorful, more fuzzy, and especially just not so maggot shaped.

But a bright color would attract more predators. Fur would trap more heat than necessary. Both characteristics would expend more nutrients to produce, and no body shape could ever be better at digging those final scraps of flesh from between the teeth of a rotting bison. Likewise, change just about anything about the adult fly, and they would never be as good at evading their predators or sniffing out those corpses to begin with.

Not only do maggots need to exist, but they need to exist exactly as they are, from mouth-hook to butt-nostril, and so do the flies who serve to deliver them by the truckload to almost everything that keels over dead on the Earth's surface.

Blue fly from Dragon Ball Online

And really, even if that weren't the case at all, even if we could live just fine without them...I just love them anyway. I love that weird, spongy tube-mouth, I love the combination of that spongy tube-mouth with absurdly massive eyes, I love the little hairs and spines all over their stout little bodies, I love their big, sticky feet, I love their buzz, I love their appetite for the junkiest of all junky foods, and I love their little meat-walrus-drill-babies. I know not a whole lot of people say this, but I'm just happy every day to live on a planet with flies on it...and I'm just going to keep on talking about them, week after week for the forseeable future. HAPPY FLYDAY!!!