A Bogleech Guide to

PLATYHELMINTHES

Written by Jonathan Wojcik 6/27/2013

The Platyhelminthes, commonly known as "flatworms," are one of those animal phyla, like the Ctenophores or Cnidarians, to have enjoyed massive success with a relatively minimal anatomy. Their soft, unsegmented bodies have no respiratory, circulatory or excretory systems, technically lacking any true internet cavities* and digesting food in a one-way, pocket like or branching gut. Their nervous system consists of a loose "nerve net" or "nerve ladder," with or without distinct ganglia towards what we can basically call the head.

*I ultimately didn't have the heart to correct my typo of "internal cavities."

The flatworms are traditionally divided into four major classes; the Cestoda, Monogenea, Trematoda and Turbellaria. Only the Turbellaria are primarily non-parasitic, and should technically be considered many smaller, similar classes in light of modern genetic evidence. The single best known and most closely studied of these are probably members of the genus Planaria, fresh-water scavengers often distinguished by their two adorably cartoonish, light sensitive eye spots. Like most turbellaria, a planarian's "mouth" is a retractable, tubular pharynx mid-way down its underside, and as simultaneous hermaphrodites, both partners are fertilized during mating.

Planarians are common specimens in High School and College biology class around the globe, where they are often used to demonstrate the amazing regenerative abilities of their phylum. A planarian, like many other platyheminthes, can be sliced into more than two hundred tiny pieces without dying, each little scrap eventually growing into a complete new animal. Partial cuts can even create temporary multi-headed worms, which eventually finish breaking apart on their own and go their separate ways.

Humid enough climates can also play host to the family Geoplanidae or "land" planaria. Often several inches in length and beautifully colored, these terrestrial flatworms are usually strict predators of other invertebrates, especially slugs, snails and annelids. Many species prey almost exclusively on earthworms, and can decimate commercial worm farms in only days.

In this gorgeous home footage from Japan, we can watch up-close how a terrestrial flatworm feeds through its sheet-like pharynx, secreting a powerful enzyme to reduce its struggling victim to a ghastly stew!

At least one species of hammer headed worm, Bipalium kewense, has invaded the United States over the past century, likely hitch-hiking in exotic house plants. As disruptive as they no doubt are, I can't tell you how excited I was to meet one of these creatures for the first time; I took the above photo around 2008, when I found myself living (not by choice) in the continent's genital region, otherwise known as Florida.

I thought wildlife like this was at least one bright side to landing in this sticky, sun-bleached hive of scum and villainy, but on a visit back to Maryland in 2011, I found three B. kewense at a park less than ten miles from my childhood home. How long could they have possibly been there? As far as I know, I'm the first person to report them from anywhere in Maryland state, though they have also been recorded as far north as Pennsylvania.

Sadly, I still find these creatures only one or twice a year in Florida, if that, and I have never seen feeding behavior in captivity.

Flatworms are still larger, more vibrant and more diverse in the sea, sometimes easily mistaken for the similarly beautiful sea slugs and nudibranchs. Famously, some species engage in a reproductive ritual referred to as "penis fencing," during which one worm will lose its penis and take on the "female" role.

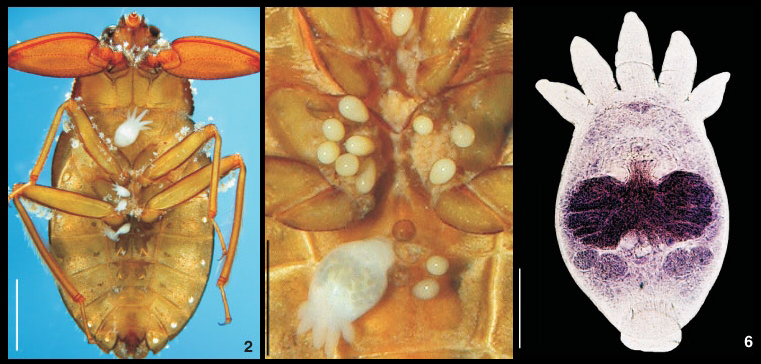

The strangest of all the "Turbellid" flatworms are perhaps the Temnocephala, distinguished by short, fat bodies and heads that branch into five or more blunt "fingers." These little cuties are sometimes internal parasites, but more commonly ectosymbiotes, living harmlessly on the bodies of snails, crawfish and aquatic insects where they feed on stray organic particles. Ectosymbiotic Temnocephalids lay surprisingly large eggs for their body size, glued to their "hosts" by short, strong stalks.

Not nearly so harmless are the Monogenea, one of the three major groups of fully parasitic flatworms. Monogeneans are largely external parasites, like leeches or ticks, armed with hooks, suckers and clamps to attach themselves to their hosts. They most commonly attack fish, though some feed on the tissues and fluids of reptiles or amphibians. At least one species specializes in the eyeballs of hippos.

In this surprisingly groovy footage, we can see just how articulated a monogenean's little talons can be. I just love how they wiggle like nasty little fingers! The larger suction appendage is, oddly enough, usually the hind end of the animal, leaving the smaller head end free to graze on the surrounding tissues and fluids.

One Monogenean, Diplozoon paradoxum, exhibits some of the most intimate monogamy in the animal kingdom; the distinct males and females pair up during the larval stage, then fuse together as they develop into adults, forming a single, seamless cross-shape with interconnecting genital ducts. The lovers can survive for many years after merging, living just inside the gills of fish where they feed on freshly oxygenated blood.

By Professor Doctor Peter Wirtz

"Seen crawling out of the anus of a freshly dead lancetfish"

Even more devoted to the parasitic lifestyle are the class Trematoda, commonly known as the flukes. Usually internal parasites, most flukes spend their larval stage in an invertebrate host - most commonly a mollusk, such as a snail - but move on to vertebrates as they mature, attacking everything from deep sea fish to tropical birds.

Unique to the Trematoda are specialized larval stages known as cercaria, whose sole purpose is to infect the next host in their life cycle. In many species, the cercaria break their way out of their original host, use a whip-like tail to track down a suitable vertebrate and tunnel their way into the flesh of their new host with a proboscis-like drilling mechanism. What a cutie, though. It may look like a tentacle demon's flesh-eating sperm, but how can those sad, beady eye spots not tug at your heart?

In Ribeiroia ondotrae, the cercaria commonly encyst themselves in the developing limb buds of tadpoles, creating severe physical abnormalities as their hosts develop into mature frogs; even complete, additional legs at odd and unnatural angles. These crippling deformities can make it difficult for the amphibians to evade their natural predators, especially the wading birds employed by Ribeiroia as their final hosts. They turn frogs into monsters, and feed them to birds.

Similarly gruesome is our beloved Leucochloridium paradoxum, practically a Bogleech mascot. These beauties need to pass from snail to a bird to complete their development, but face two problems: not only do snails spend most of their time hiding in the dark, they aren't particularly appetizing to most birds. Fortunately, the parasite can kill two birds with one stone (or infect one bird with one snail, anyway) by growing a set of colorful, throbbing "brood sacs" into the snail's eye stalks.

By Hanne Sundin - more gifs and invertebrates under link!

Bloated with cercaria, the brood sacs serve the dual purpose of inhibiting the snail's vision and imitating a pair of maggots or caterpillars. The "blinded" gastropod eventually crawls out into the open, oblivious to the daylight, and gets its face ripped right off by a passing avian. It can often survive this attack, slowly regenerating its tentacles, but so does the parasite. Its true body lies deeper within the snail, and it will soon have a new set of brood sacs ready for round two.

Words fail to capture just how much joy these particular creatures bring me. Nothing in life could be more magical than a parasite transforming a snail into false maggots only to be eaten over and over. I opened the internet's only Leucochloridium fan-art gallery more than six years ago, and the entries still fill me with more pride than almost anything else on the site.

Yet another famous body-snatcher is Dicrocoelium dendriticum, also known as the lancet fluke. In this case, the cercaria are coughed up by snail hosts in small balls of mucus, which seem to be exceptionally appetizing to ants. Infected ants are then driven to climb blades of grass, clamp onto the tips with their jaws, and wait there patiently until swallowed by a grazing mammal. If this still hasn't happened when the sun begins to set, the parasite releases its control and the ant returns to its colony, repeating the attempted sacrifice day after day.

While they may not turn our eyeballs into caterpillars or feed us to cows, many flukes are capable of parasitizing us humans, the most devastating of which are the Schistosoma or blood flukes. No fancy mind control, here; cercaria develop in aquatic snails, contaminate the surrounding water and burrow directly into the flesh of birds or mammals, migrating to the bloodstream where they mature and reproduce. Unlike any other trematode, they exhibit distinct male and female sexes, and like Diplozoon, they usually mate for life. The broad, flat male folds himself lengthwise around the body of the longer, thinner female, and the two may remain in this tender embrace for over twenty years, adrift together in a giant's blood, like a microscopic taco having perpetual intercourse with its own filling.

Sometimes I feel really tempted to just start writing erotica.

Blood flukes wouldn't actually cause that much harm if it weren't for that constant lovemaking; it's their spiny eggs, released directly into the blood, that trigger severe immune reactions and are responsible for the disease Schistosomiasis. These eggs are passed by the body in urine and feces, where they eventually find their way back into the water supply and infect a new batch of snails.

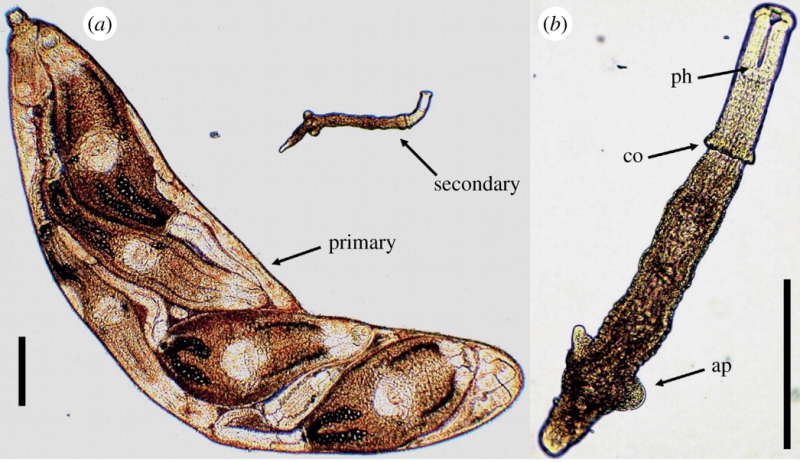

One incredible and relatively unexplored characteristic of some Trematoda is the existence of a caste system, like we see in ants or termites. On the left, we see a reproductive morph, bloated with several fully formed cercaria. On the right, far tinier, is a non-reproducing "soldier" morph, created by the parasite to attack other, competing flatworms in the very same host. The soldier's tubular pharynx (ph) is its weapon, used to "bite" into rival reproducers or swallow their own small warriors whole. Much more on this awesome colonial lifestyle can be found here!

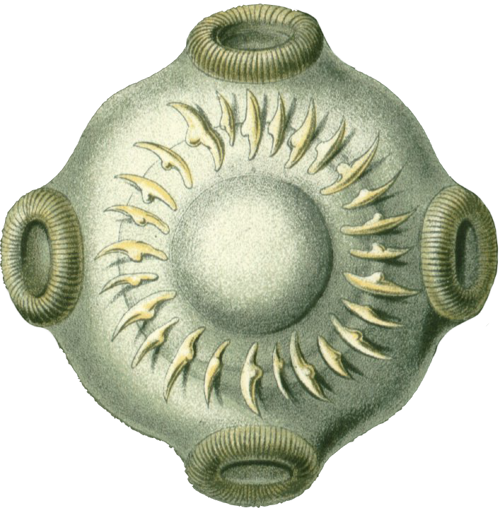

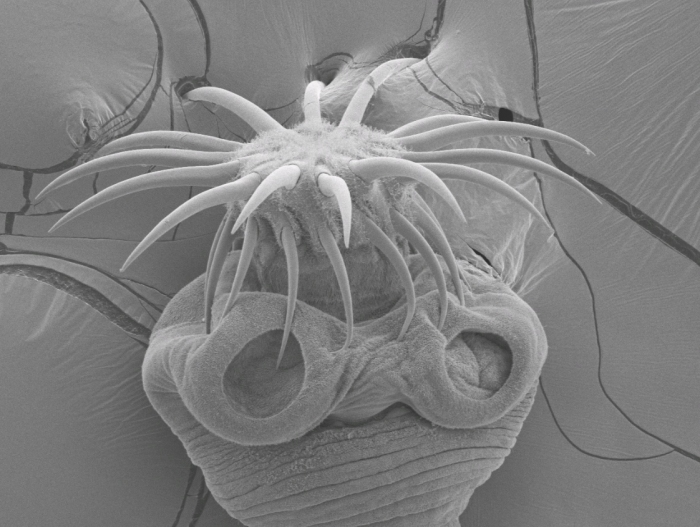

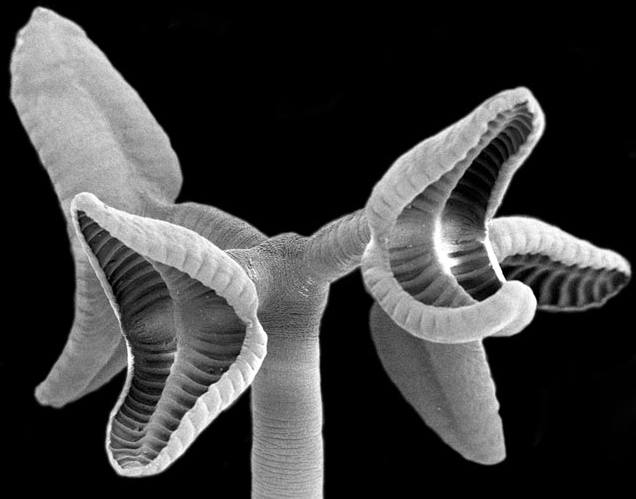

Leaving behind the flukes, we come at last to the class Cestoda, otherwise known as the tapeworms. These intestinal serpents are easily the most widely famous endoparasitic worms, and among the most anatomically peculiar beings in the animal kingdom. What our minds want to identify as a "head" is really nothing more than a barbed and sucker-lined anchoring appendage, properly known as the scolex, (above) which appears to begin as the rear end in the animal's earlier stages. The rest of the "body" is more accurately described as a repeating chain of complete, individual clone bodies, or proglottids, forming a sort of "colony" called the strobila. Lacking a mouth or gut, the entire organism absorbs nutrients directly from the host's digestive tract, functioning almost like one inside-out intestine itself.

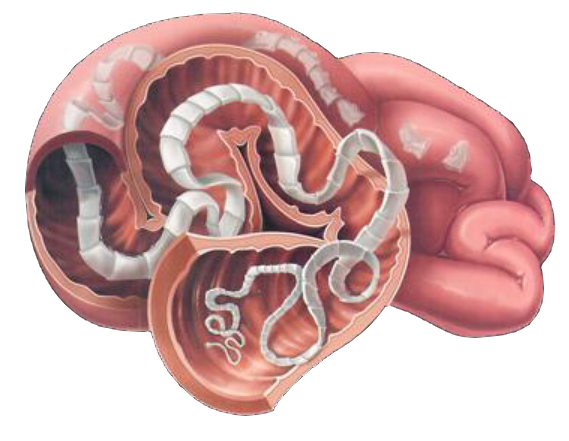

As new proglottids grow from the base of the scolex, old proglottids break off from the opposite end and allow themselves to exit with the host's feces. A single proglottid can contain thousands of microscopic eggs, and these can contaminate the surrounding soil, water and grass until ingested by their first host. In the case of terrestrial tapeworms, this obviously tends to be a grazing, grass-eating animal, such as a sheep, cow or pig.

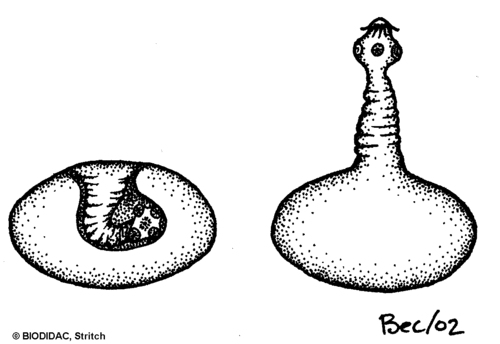

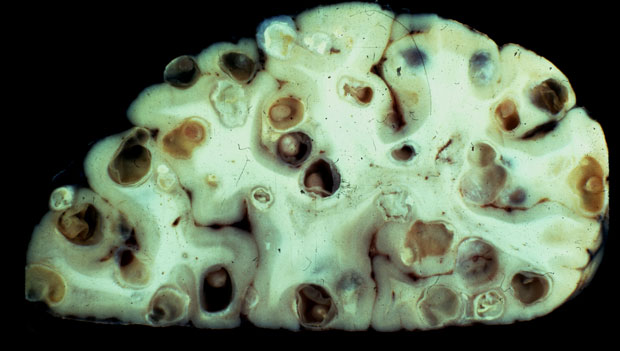

When eggs are ingested directly, they hatch into Cysticerci or "bladder worms," nearly spherical larvae who wriggle their way through the body and usually try to embed themselves in muscle tissue, forming hard cysts to shield themselves from the host immune system.

The cysticerci continue to slumber in the host's tissues until they are swallowed by a carnivore, which can occur even after the host has died of natural causes and attracted scavengers. When an animal swallows cysts rather than eggs, the bladder worms awaken from their stasis, travel from the stomach to the intestines, embed their scolexes and begin development into the adult worm.

As omnivores, humans can become infected by tapeworm at every stage of this cycle; if we ingest the cysts from contaminated meat, we become hosts to the adult worm. If we swallow eggs from dirty water, contaminated vegetables or contact with someone incredibly unhygienic, the emerging bladder worms attempt to form cysts in our meat. The latter isn't a natural part of their life cycle, and the "confused" worms may end up almost anywhere in the body - including the brain or eyes. This is why we wash our hands and cook our bacon.

Scolex of a Rhinebothrium tapeworm, parasites of stingrays. Photo by Claire Healy

I know I almost always say something like this, but only because it's almost always true: for all the weird stuff we've seen on just this one little internet page, it's barely the briefest glimpse into the alien wonders populating this ancient phylum. More than 20,000 individual species of flatworm have been documented, over half of them parasitic, and tens of thousands more are undoubtedly slithering their way through unexplored swamps and exotic entrails as we speak.

No matter how horrified you may be by their methods, you have to appreciate the sheer lengths these creatures have gone through to survive. They've been here since the Cambrian, and they'll probably be here a lot longer than us; disintegrating earthworms, fencing penises and feeding animals to other animals as they see fit.